The world and the U.S. are still processing the implications of Donald Trump’s return to the White House. In this essay, I do not mean to belittle the many deeply troubling concerns regarding Trump and his second term. However, amid all the noise, there are elements of what might be called normal politics for which the 2024 election marked an important pivot. AI is one such area. There were no campaign ads touting Trump’s AI policies, but it was a central issue for a small but influential constituency of tech leaders and investors that played a major role in Trump’s victory.

In contrast to the first Trump Administration, where tech issues were an afterthought, the group now poised to take power has a detailed and aggressive view about where to take AI policy, and the human capital to make it happen. Moreover, since 2016, and especially since 2022, AI has become dramatically more important for economic, national security, and foreign policy. We are at a pivotal moment for both AI adoption and AI governance, which may shape the technological environment for decades to come. The stakes are higher than most realize.

As someone who has been in and around US tech policy for 30 years, I see far too many observers falling back into their conventional assumptions about how AI regulation will play out. We may be surprised. This is the first in a series of posts on what we can expect in AI policy in the next four years.

There is much I disagree with in the Trump 2.0 AI agenda, not to mention the angry, swaggering triumphalism of many of its acolytes. However, it deserves to be taken seriously, not simply viewed through the prism of Trumpism. These essays will outline what I believe is likely to happen, not what I think should happen. And while nothing is certain, given Trump’s erratic behavior and penchant for turning on his friends, there is reason for hope that the new direction in AI policy might turn out to be one of the second Trump Administration’s most positive legacies. It shares significant intellectual roots with the Gore-Clinton-Obama tech policy approach, and potential continuity with a valuable dimension of the outgoing Biden Administration’s AI actions.

It’s a risky bet, to be sure, which will certainly open the door to greater harms from AI. But it’s also an optimistic vision of supercharging socially and economically valuable innovations, while perhaps leaving space to address the negative consequences through other means. Perhaps.

Return of the Techies

The Biden Administration’s initiatives on AI were excellent and substantive, despite a polarized environment in which Congressional action was unlikely. As in so many other areas, the Administration got little credit for its work. What was always missing was a visible senior official, ideally the President or Vice President, taking a personal interest and making tech policy a focal point of the White House agenda. The Clinton and Obama Administrations were tech Presidencies. The Biden Administration’s head was in the right place, but it was not technocratic at heart, at least at the top. The work fell to immensely talented senior staffers such as Alondra Nelson and Arati Prabhakar at the Office of Science and Technology Policy, who were largely invisible to the general public. That gave them and their teams scope to do fine work, including on AI, but it meant the Administration never truly embraced the significance of its AI policies.

Trump himself is hardly tech-minded. However, the incoming Vice President, J.D. Vance, who spent time as a venture capitalist and is close to the circle around tech investor Peter Thiel, is. Tech policy in the first Trump Administration, while not prioritized, was led by respected figures with industry experience such as Michael Kratsios, the former U.S. CTO, who is involved in the current Transition. And the small but powerful cadre of Silicon Valley figures, including Marc Andreessen, David Sacks, Shervin Pishevar, Keith Rabois, Shaun Maguire, and most notably Elon Musk, who went all in for Trump this time did so to promote an agenda they now fully expect to implement.

The Trump 2.0 AI Agenda

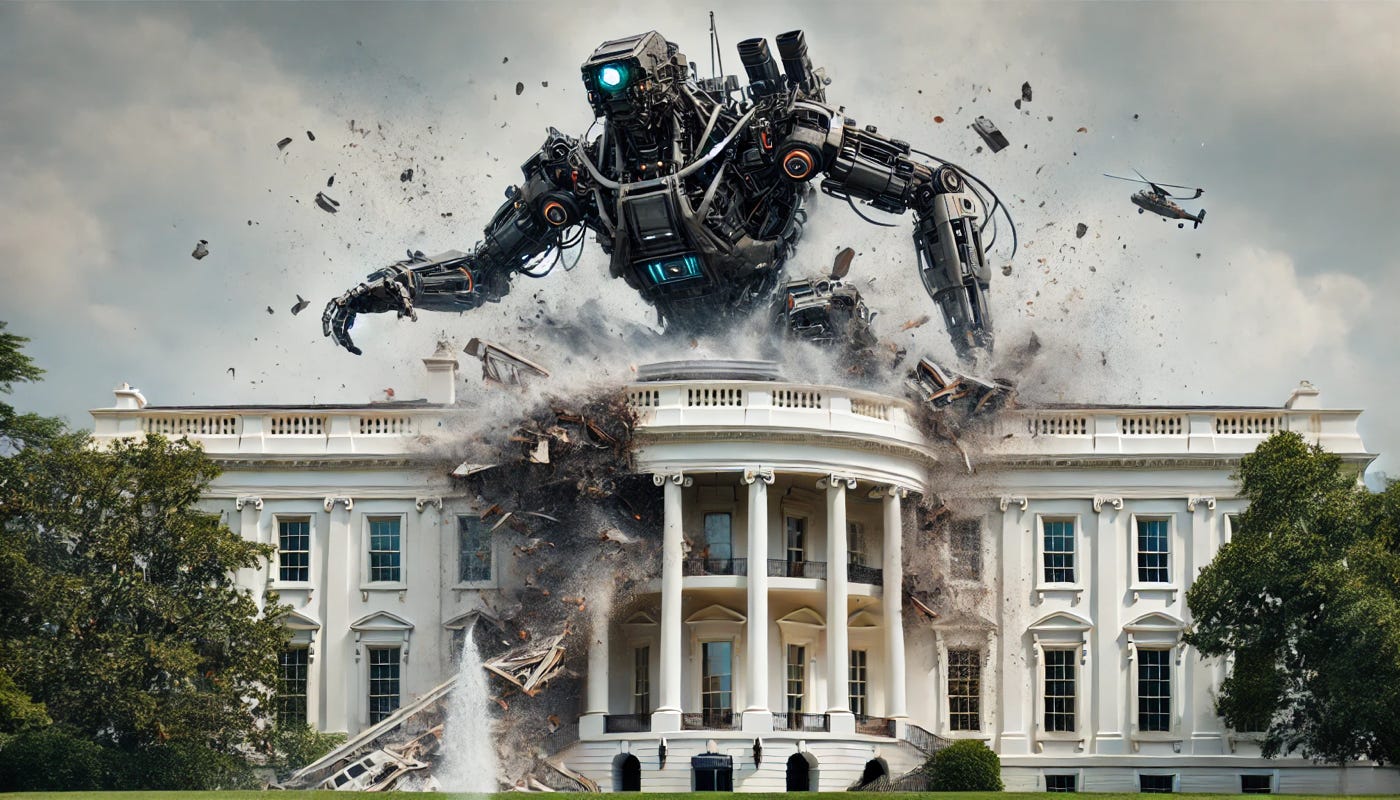

The central goal of the Trump 2.0 AI agenda is to unshackle American AI development from the perceived regulatory and ideological restraints that stand in the way of an American-dominated AI utopia.

That means repealing and replacing the Biden Administration’s sprawling and consequential AI Executive Order from a year ago. The EO imposed a web of requirements on federal agencies and promoted standards processes to influence private sector AI development indirectly. The Trump team sees these as bureaucratic impediments that will prevent AI companies from realizing the potential of the technology, and eventually cede global leadership to China. They seem to view them similarly to the European Union’s AI Act and General Data Protection Regulation, comprehensive regulatory regimes that impose detailed compliance burdens in order to protect fundamental rights and mitigate risks. There will likely be something more modest adopted, building on the Trump Administration’s 2019 AI Executive Order, which the Biden Administration left in place.

Alongside the reorientation of White House policy will, no doubt, be a significant reduction in the aggressive enforcement actions by administrative agencies and Executive Branch departments regarding algorithmic bias, as epitomized by the FTC’s sanctions against Rite Aid over its use of facial recognition and the Administration’s initiative against discriminatory housing valuation algorithms. Any investigations involving harassing or toxic AI-generated content, as well as misinformation and manipulation, are likely to be shut down aggressively, given the Trump 2.0 crowd’s intense critique of what they consider censorship. Privacy protection will also be de-emphasized. Antitrust is less clear. Vance has praised Biden FTC Chair Lina Khan’s attacks on concentrated corporate power, Trump-supporting venture capitalists such as Marc Andreessen promote “little tech” startups, and the management and employees of many tech giants lean left. Trump 2.0 will undoubtedly make it easier for startups to sell out to big tech players, which has been a point of contention under the Biden regime.

One of the most significant legal flashpoints for AI policy is not regulation, but judicial decisions regarding intellectual property. Many lawsuits by content creators argue that generative AI firms wholesale scraping of copyrighted material for training exceeds the bounds of “fair use,” and that outputs of their systems are infringing as well. Given statutory damages of up $150,000 for each incident of willful copyright infringement, this represents a potentially existential threat to major AI foundation models.

While it’s a matter for the courts, the Trump Administration could push for Congressional action creating a text and data mining (TDM) safe harbor in copyright law, which some are calling a “right to learn.” Japan already has such an exception, which AI companies have used to defend their scraping practices, and legislation could impose some minimal obligations along the lines of Section 512 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, which addressed similar concerns about user-uploaded or user-generated content on the internet. Though there are strong forces on the side of strict copyright enforcement, they are concentrated in industries such as the media and entertainment that skew Democratic, and thus will find their positions holding less weight under Trump 2.0.

Elements of Self-Regulation

In the place of direct regulation of AI systems, the new Administration will lean on industry-based coordination and certification efforts. The details of this direction come from Trump-aligned policy papers outside the campaign. However, a move toward industry self-regulation is a logical step for Trump 2.0 AI policy. Major AI companies themselves have been saying for years that there are serious issues around alignment, accuracy, and safety of their models, which they acknowledge deserve careful attention. There need to be ways to establish baseline practices that companies are expected to engage in, and to compare among different models. And while the Trump crew may not so be concerned about algorithmic bias, they are likely to worry about cybersecurity and attacks by hostile state-sponsored actors.

Fortunately, this kind of industry-driven activity is already happening. In some cases it is shepherded by government entities such as the National Institute of Science and Technology in the US or the European standards agencies tasked with implementing the EU AI Act. In others, key industry players are coming together on their own, or under the auspices of trade associations and academic research centers. Stories about AI models hallucinating, leading teenagers to suicide, or unfairly discriminating don’t help establish trust in the marketplace. Companies do have incentives to take some level of care, and to do so in coordinated ways to overcome collective action problems.

Self-regulation, in whole or in part, is a legitimate mechanism employed successfully in important fields, such as finance. But there is always the danger that, lacking real teeth from possible regulatory sanctions or guidance from prescriptive government-imposed rules, it will devolve to a least common denominator system that puts no real pressure on industry to mitigate harmful and dangerously risky activities. There are differences within the private sector, with Elon Musk’s X.ai staking out an “anything goes” position and more established firms such as Microsoft, Google, IBM, and Salesforce promoting serious accountability for AI systems, even without government mandates. The Trump Administration may be reluctant to exercise the kind of robust oversight that ensures self-regulatory organizations such as FINRA for broker-dealers in financial markets are effective. But once such structures are established, they create foundations that can be built upon.

There are plenty of tensions within the Trump 2.0 coalition that could take its AI policies in different directions. As this initial essay hopefully makes clear, though, even though the new Administration has the traditional Republican skepticism of regulation, it is not simply a continuation of Regan-Bush-Bush deregulatory neoliberalism. We’re in for something new. All of these actions will be targeted at turbo-charging American AI development, with the expectation that under the right conditions, innovation and adoption will explode.

To Be Continued

This is the first in a series of posts about the AI governance policies we can expect from the incoming Trump Administration.

In Part II, I will take up the aspects of Trump 2.0 AI Policy beyond removing restraints on the private sector. Some AI companies may actually find themselves under attack by the new White House.

In Part III, I will examine where the Trump 2.0 approach to AI may, surprisingly, represent a continuation of the Biden approach.

In Part IV, I will play out what will likely happen next, beyond the actions of the new Administration.